Local Matters: Early Housing Experiments with Earth in Morocco

essays

Jan 25, 2026

Mourad Ben Embarak, the first Moroccan architect to join the Service de l’Urbanisme after independence, articulated the problem of defining a “modern Moroccan architecture” (1). While condemning both pastiche and the eclectic citation of historical forms, he questioned how “traditional” architecture could be referenced within modern construction. His formulation of the question reveals a fundamental separation deeply rooted in colonial and orientalist logic: traditional architecture was still seen as external to modernity, its value to contemporary practice reduced to a mere citation or image. This tension was not unique to architects. Moroccan youth more broadly expressed a desire to live in spaces and environments that embodied progress, simplicity, and logic—a universal language of architecture that nonetheless retained an original Moroccan character (2). Intellectuals and artists engaged in cultural and political circles echoed this position, calling for the autonomy of cultural expression beyond colonial or bourgeois ideology. As one such statement insisted, “much of our culture did not reflect the ideology of these exploitative classes and had been expressed for centuries, if not millennia, in specific, autonomous, oral and collective forms that were integrated into everyday life. This was true then and remains true today of our vernacular rural and urban literature, music and popular art” (3). This essay traces how architects in Morocco experimented with concrete strategies in the search for the meaning of vernacular practices applied to the project of Moroccan Habitat.

Until the mid-1960s, the Moroccan state systematically intervened in housing, largely continuing the French Protectorate’s framework. Initiatives such as the Derb Jdid housing scheme in Casablanca by Moroccan architect Elie Azagury adapting the Écochard grid (vertically and horizontally) to residents’ income levels (4), or the reconstruction of Agadir post-earthquake underscored architecture’s role in nation building and self-determination (5).

Housing shortage in cities also inevitably called for planning in the country beyond the productive lands of the Maroc utile (“useful Morocco”) (6). Town planning extended to infrastructure projects and norms for new rural centres were drafted to strengthen the “rural armature” throughout the country (7). In the following decade (1965–1975), however, housing budgets fell sharply—from 54 to 8.5 million dirhams—due to economic and political turmoil requiring a drastic reduction in direct state action (8). The assisted sanitary grid (Trame Sanitaire Assisté) consisting of roadways, sewage, and electricity connection exemplifies this shift: a basic infrastructure for beneficiaries of the plots to carry out their own housing project (9).

The scarcity of resources forced the Moroccan state to seek funding through international aid agencies such as IBRD, WFP, UNDP, or UNICEF. Diagnosis, reporting, and research on housing became essential leverages for funding. To this aim the Centre d’Expérimentation, de Recherche et de Formation was established in the urban planning and housing department (10) under the Interior Ministry. This think tank composed mainly of foreign experts (architects, engineers, and social scientists) connected Moroccan experimentation to an international discourse on self-construction, vernacular studies, and urban planning. Through critical bibliographies and magazine subscriptions, the research group was familiar with the works and ideas of figures such as Hassan Fathy, Bernard Rudofsky, John Turner, or Doxiadis (11).

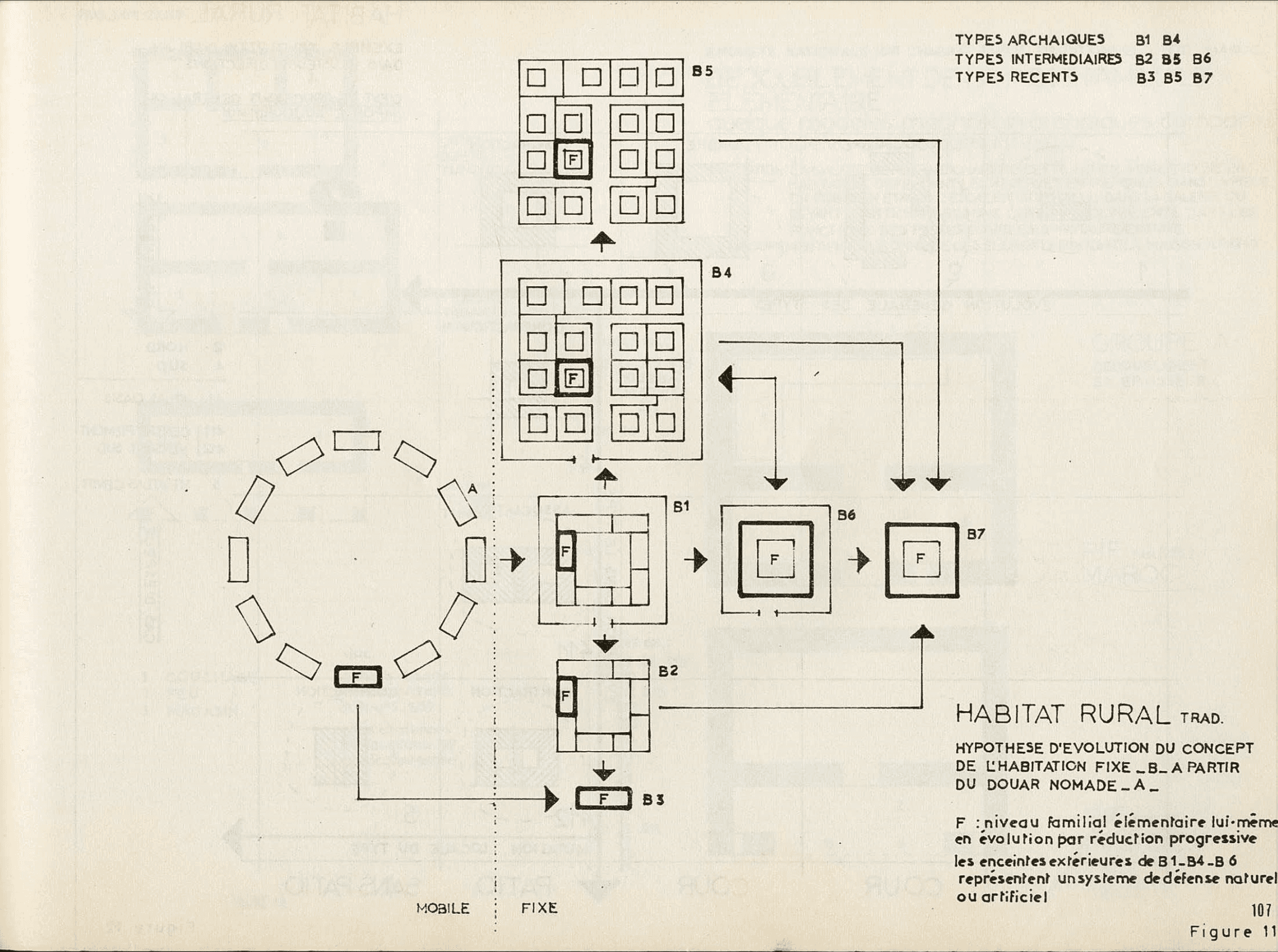

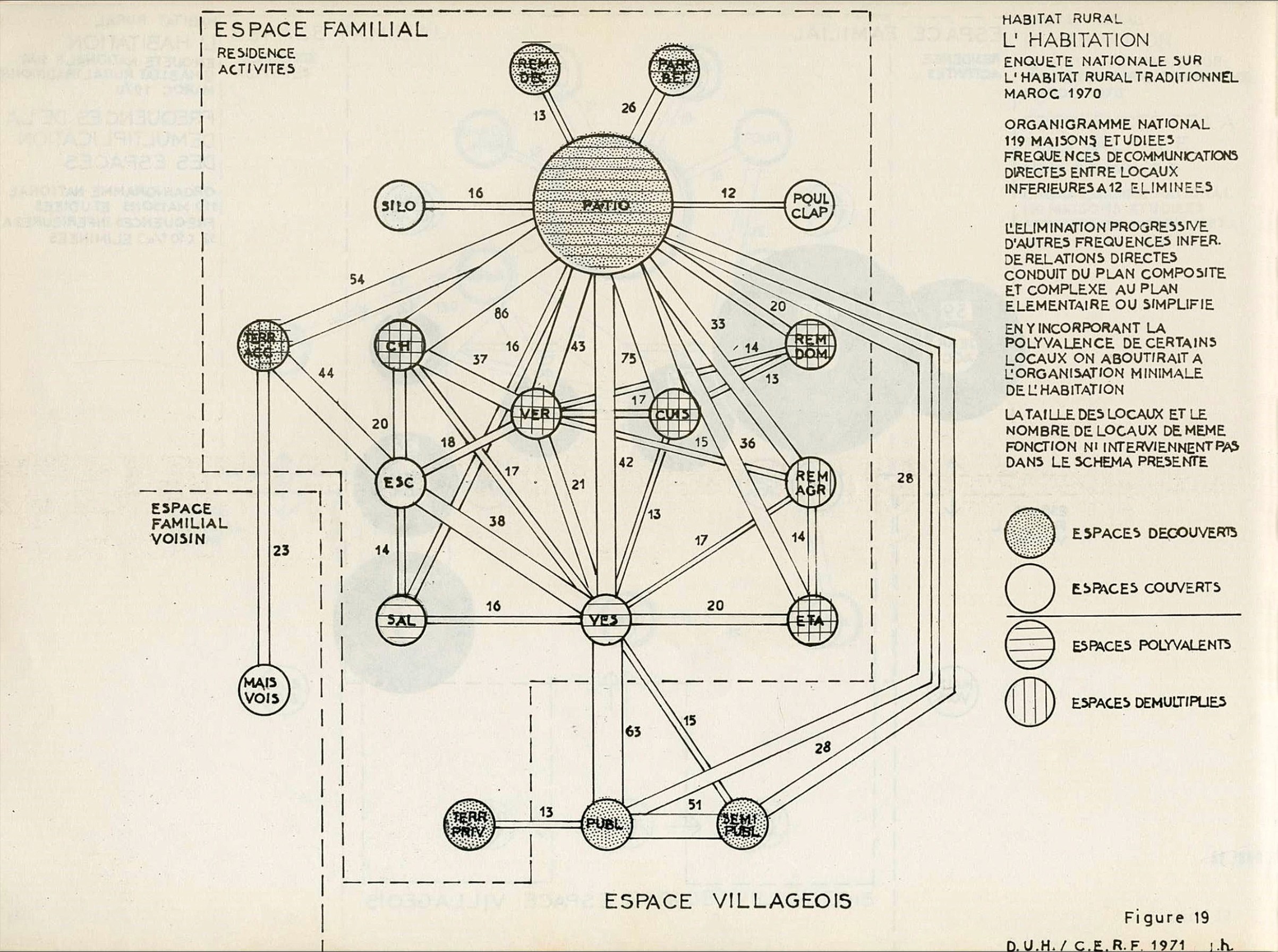

Building With / Renovating the Existing

The never-ending housing question fuelled by decades of rural exodus towards the industrialized Atlantic Coast had eclipsed until then an important corollary: the erosion of social and material structures in villages marked by departures and abandonment, especially in the mountainous and desert regions of the country. The realization that rural architecture was a “tradition in peril” (12) at a moment of post-colonial self-determination led to efforts of documentation and preservation. The most significant project is a national survey on vernacular domestic architecture (habitat rural traditionnel) (13) conducted by Belgian architect Jean Hensens working within the CERF together with Moroccan students of architecture, geography, and sociology. The research was compiled in 1970 into a publication entitled Habitat rural au Maroc: Enquête sur l’habitat rural traditionnel. Beyond systematic orthographic drawings to scale (plans, sections, elevations) and numerical data on construction costs and materials, this national inquiry attempted to systematize the evolution of housing principles and space use within the family unit and the collectivity at large. The stated purpose of the study beyond documentation and analysis proposed a “prospective model,” i.e. a set of norms and considerations according to which existing rural habitat could be enriched and renovated using modern means echoing inhabitants’ aspirations (14). This project embodies multiple layers of contradiction: it is a national initiative led by a foreign expert; a central operation advocating for regional autonomy; a modernization project holding the “naïve” belief that progress is gradual and selective (15). Yet, it offers a lens through which to understand the ethos of the mass housing project that took place in the 1965–1975 decade and the position of architects involved in the field vis-à-vis the state position.

Building with Local Materials

The interest in rural habitat and its modes of construction opened a field of research within the CERF on how mass housing projects could experiment with local materials by industrializing “traditional solutions” (16). This line of inquiry was supported by a reciprocal argument: the enduring modernity of “volumes, plans and traditional materials” (17) and the “most modern methodology in the service of the most traditional habitat” (18). This orientation fostered technological experiments aimed at improving local materials such as earth and reed, cast as free resources (19).

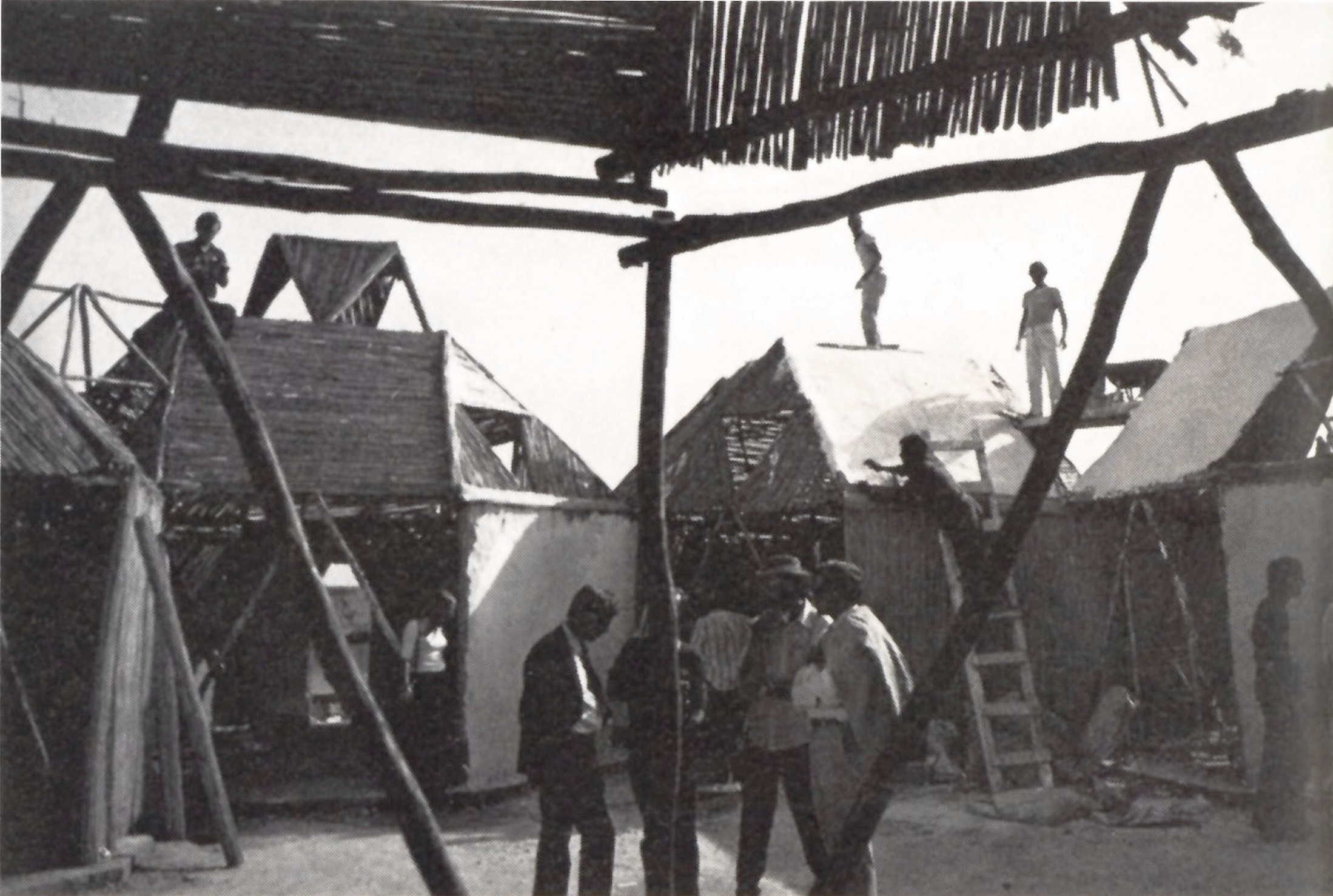

A line of research explored the potential of reeds and plaster to deploy lightweight, reproducible solutions using reeds and prefabricated elements, as a slum-upgrading scheme (20). The experimentation culminated in a building seminar (21) involving Moroccan, French, and American students and local labourers in Rabat’s Yacoub El Mansour neighbourhood where slum clearance was underway (22). The experiment consisted of 25 m² single octagonal room units assembled with intermediate water closets to enclose a circular central court. The units were seen as multiple rooms for a large household or single-family units choosing to live together. While the seminar was championed as a pilot construction site towards a larger construction movement in the neighbourhood using reeds and plaster, community involvement was minimal. Knowledge transmission through various awareness measures, technical assistance, and affordable material supply were mentioned in principle but not acted upon (23). The emphasis fell less on meaningful co-production than on showcasing reproducible forms using local materials and methods, underlining a paternalistic approach that oscillated between valorizing tradition and imposing functionalist modernity (24).

Another line of research attempted to serialize rammed earth construction in service of permanent mass housing solutions. For instance, a project in Ouarzazate in 1967 delivered 200 housing units made of cast-in-place stabilized earth concrete (béton de terre stabilisé), giving its name to the operation: BTS-67 (25). Alain Masson (engineer) and Jean Hensens (architect), leading the project, wished to speed up the construction process while reducing the amount of skilled labour required: metal formwork replaced wooden benches, pneumatic tampers accelerated compaction, and entire units were cast monolithically with walls and vaulted ceilings in a single operation (26). At the scale of the housing unit, BTS-67 extended to a 10 m by 10 m perimeter incorporating spatial devices such as a chicane entrance for more privacy, a courtyard with a garden, and even a dedicated space for cattle. Hensens’ detailed drawings of prefabricated elements such as gargoyles, water basins, and alcoves for furniture made of reeds reveal a careful observation of dwelling practices, from everyday objects to modes of circulation within the home (27). The vaulted roof, however, proved alien to Moroccan dwelling patterns, as it prevented vertical extension, and was ultimately abandoned after the first few prototypes were built, replaced by a flat reinforced concrete roof (28).

The tension between representation and lived reality was also visible in the way the project was documented: photographs of the construction site highlighted the machinery, formwork, and technical reproducibility, while effacing the presence of workers, as if modernist form-making itself was the true subject of the experiment (29). Moreover, the scheme itself embodied a deeper ambiguity. Typologically, it translated rural architectural elements into an urban housing complex, but the absence of electricity and glass windows left it suspended between the temporary and the permanent, the rural and the urban. As Rouizem observes, BTS thus embodied the contradictions of such projects: attentive to traditional ways of life, yet conceived through a modernist lens that privileged technical reproducibility and economic assessment over ecological or social sustainability (30).

Building with the People

Understanding the limitations of a purely technical or material approach, members of the CERF reflected on the possibility of people building their own durable standardized dwellings. Aligned with the international discourse on “aided self-help housing” (31) promoted by foreign aid agencies, they sought to empower unskilled communities to shape their own built environment, provided with adequate tools and guided by the right expertise (32).

In Morocco, the rhetoric of self-help found resonance in the colonial ideal of the peuple bâtisseur (the building people), most clearly expressed by the late Protectorate in the Castors operations (33, 34). First initiated in France in the late 1940s, the system was transposed to Morocco in the 1950s as part of “indigenous” housing programs (35). Moroccan Castors were called upon to build their own homes, with plots and plans supplied by the authorities, thereby lowering costs through the mobilization of unskilled labor (36, 37). After independence, this model resurfaced in a new guise through the Programme d’Habitat Rural (1968–1972), supported by the World Food Program. Rather than receiving subsidies, rural communities were asked to contribute their own labor in exchange for food, in a context of declining state involvement under economic and political constraints (38). Influenced by John F. C. Turner’s “sites and services” experiments in Peru—which Turner himself presented to the CERF in Rabat—Moroccan planners promoted progressive improvement of equipment through incremental self-construction rather than clearance followed by eviction (39). Two types of “food-for-work” actions were conducted (40): first, the renovation of houses within the Qsur reframed as both touristic and cultural assets to be continuously inhabited and maintained (41); second, the construction of new homes through self-help with only minimal technical and material assistance (42). The CERF promoted these programs as grounded in people’s will and building know-how, yet in practice, plans and schedules were imposed by experts, leaving little room for genuine participation (43). This contradiction highlights the ambiguity of self-help: celebrated as decentralizing, modernizing, even decolonizing, it remained entangled with dependency on foreign expertise, imported technologies, and the withdrawal of the state (44).

Building without Plan

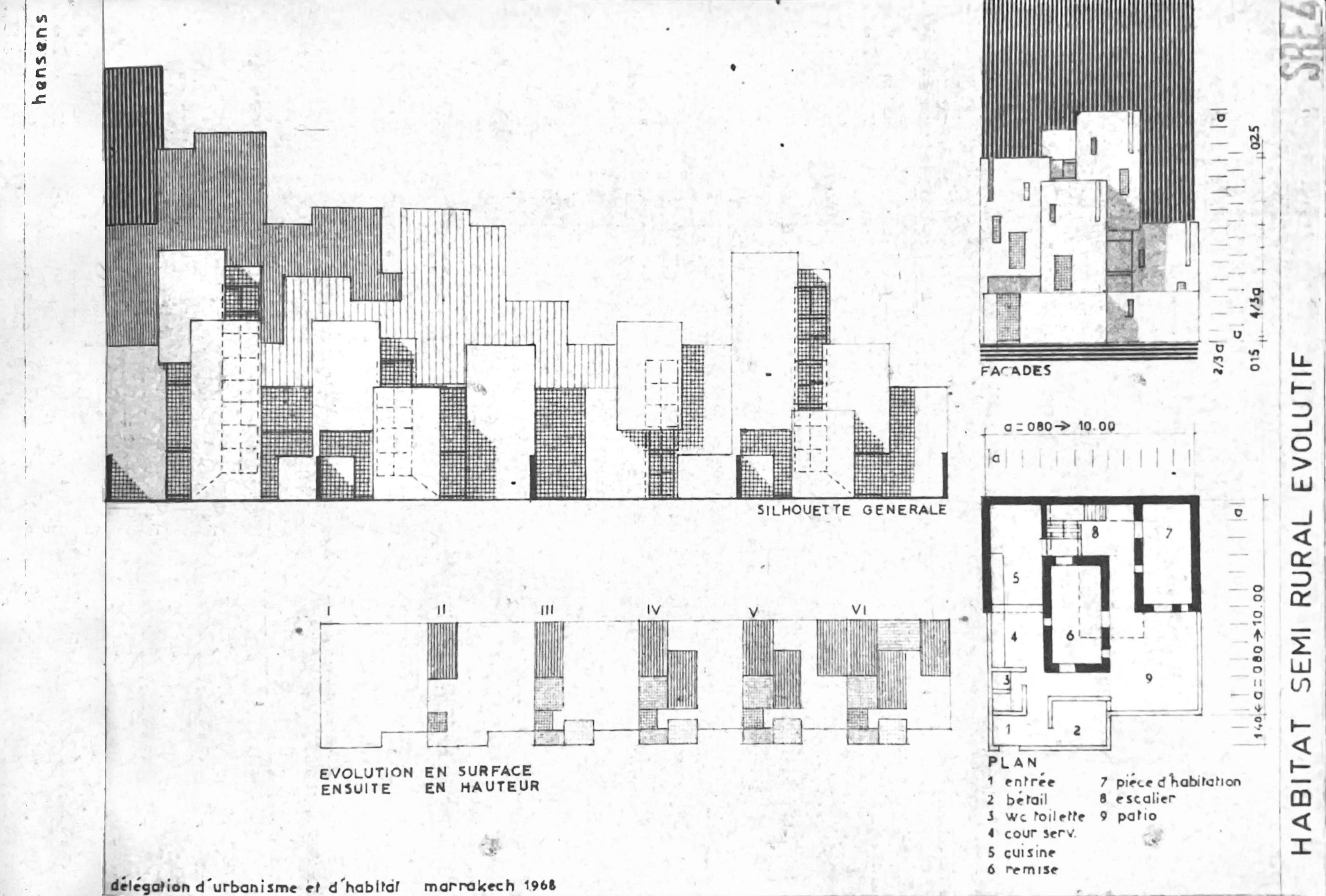

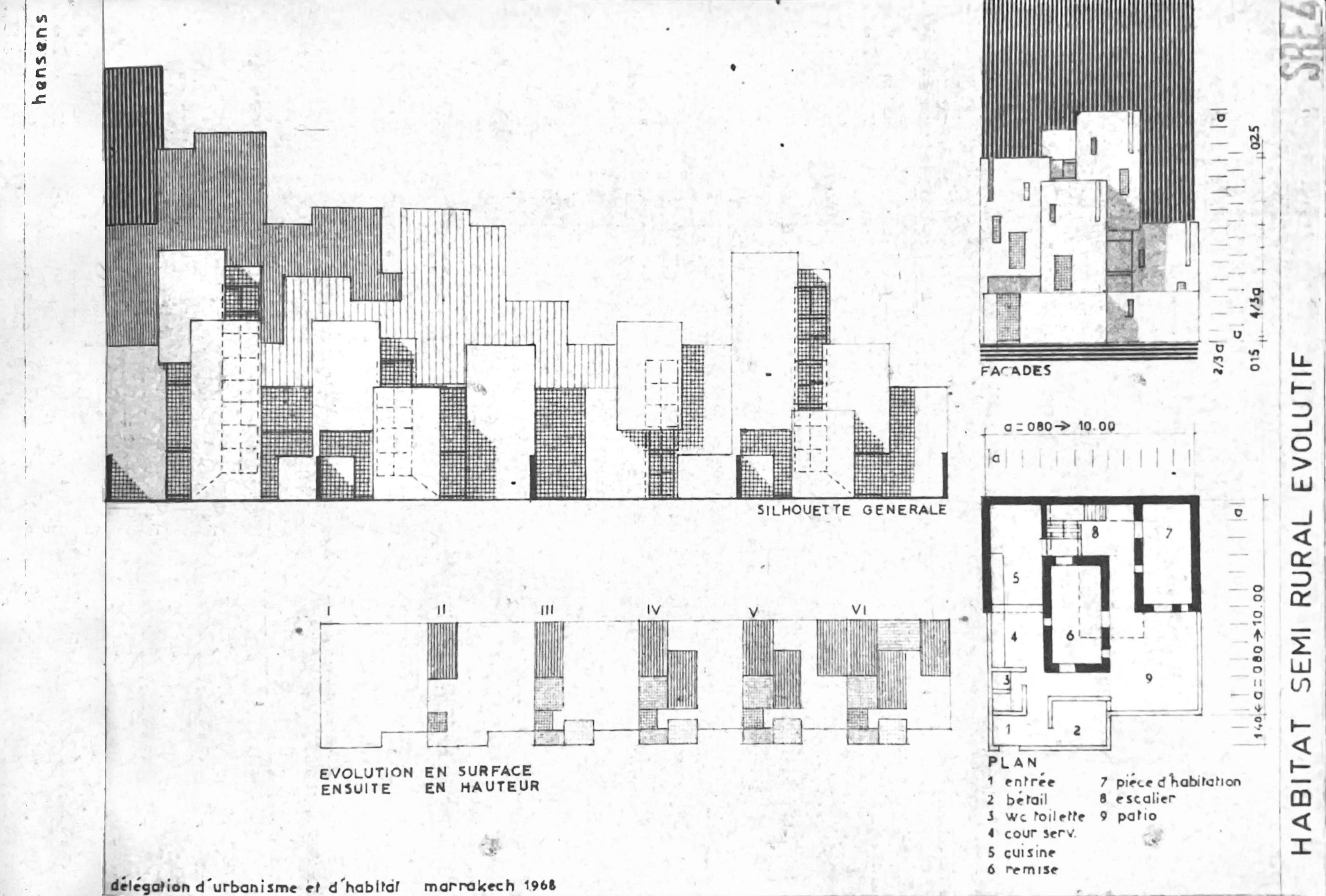

Within the CERF, architects like Jean Dethier or Jean Hensens became increasingly critical of the shortcomings of planning policies, realizing their mission to modernize the countryside risked erasing all intermediaries between the nuclear family and the village (45). An unrealized design proposal in 1970 by Jean Hensens can be read as a counter-project to the State’s grappling with the complexity of local matters: the Habitat évolutif auto-construit normalisé.

This scheme reflected the architect’s will to withdraw: “a massing plan without plan” (46). Instead of a fixed design, it offered a series of norms and prescriptions at multiple scales. Direction of growth was indicated, with zones for self-construction and equipment envisaged at the block, neighbourhood, and city level. Within the housing unit, families were allowed to expand in plan or height—a continuation of the research on evolving habitat conducted as part of the BTS-67 operation. The presence of the “typical plan” appeared more as evidence of the architect’s awareness of local practices, a token of legitimacy rather than a blueprint (47).

At the core of these positions lay a concern with language. Hensens often described architecture and urbanism as part of a common “vehicular language, intelligible and elaborated by all” (48), or as Amos Rapoport wrote in the same years, a framework of constraints and loose rules allowing the interplay of constant and changeable aspects of human life (49). The institutionalized vernacular building, as Rapoport argued, was reduced to linear progressions and historicist clichés (50). The industrialized vernacular, a “heterogeneous art” and “truest expression of Moroccan architecture,” as Hensens explained, was impoverished and unsightly (51). From this ground, he believed, a genuine mutation could emerge, combining tradition with new techniques.

Yet such a model, he insisted, could only function under decentralized management: a return to village autonomy, not through the revival of traditional assemblies—which risked cultural inertia—but through new local bodies capable of transmitting know-how and coordinating collective building (52). This amounted to what Hensens later described as a “decentralist social utopia,” a counter-model to the universal industrial city of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (53). The implications of such a social order extended to property structures. Colonialism had introduced divisibility and private appropriation into Moroccan landownership, undermining collective forms of property (54). For Hensens, however, collective frameworks that resisted fragmentation remained a critical condition for sustaining endogenous processes of space-making. In this system, the architect was not an expert or technocrat, but a participant in the communal project through an “integrated technicity” that drew on collective principles while opening to modern needs (55). Even the existing built environment was not exempt: it too had to evolve with contemporary uses. As Hensens put it, the task was not nostalgic preservation but the study, deepening, and updating of communal principles within urban policy (56). The goal was not the maintenance or fabrication of a static “traditional” architecture, but what he called an architecture en devenir traditionnel—becoming traditional—shaped by collective life, external contributions, and creative activity (57).

The end of the Programme d’Habitat Rural and the dissolution of the CERF in 1973 coincided with a gradual decline of the state’s direct intervention in mass housing projects. The activity of the research group was entangled in colonial and post-colonial practices, as its staff—composed mainly of foreign experts—acted at once as agents in the field for the Moroccan state and as bridges with foreign agencies (58). The extensive research material produced in the preceding decade nonetheless attests to a genuine concern with recovering the tacit knowledge and values embedded in minor architecture toward an alternative political project.